Understanding Adverse Event Rates: Percentages and Relative Risk in Clinical Trials

Feb, 7 2026

Feb, 7 2026

Adverse Event Rate Calculator

Group A (New Drug)

Group B (Control)

Results

When a new drug hits the market, everyone wants to know: is it safe? But safety isn’t just about whether someone had a side effect. It’s about how often it happens, and under what conditions. Two people might both get a headache after taking the same medicine - but if one took it for 3 days and the other for 3 years, the real risk is totally different. That’s why simple percentages can be misleading. The FDA and top drug companies now rely on more precise methods to measure risk, and understanding these tools helps you make sense of what’s really going on in clinical trials.

Why Percentages Alone Don’t Tell the Whole Story

You’ve probably seen headlines like: "15% of patients in Trial X had nausea." That sounds clear - until you realize half those patients were on the drug for 2 weeks, and the other half stayed on it for 2 years. The percentage doesn’t change, but the actual risk does. This is called the incidence rate (IR): total number of people who had the event divided by total number exposed. It’s easy to calculate, and for decades, it was the standard. But it ignores time. If you only look at IR, you’re essentially saying a 3-day exposure equals a 3-year exposure. That’s like saying a 10-minute drive and a 10-hour drive have the same chance of a flat tire.

A 2010 analysis by Dr. Cate Andrade found that using IR alone could underestimate true event rates by 18% to 37% in trials where treatment lengths varied. Imagine a drug for chronic pain. People on placebo stop after 6 months. People on the new drug stay on it for years. If 5% of the placebo group had liver issues over 6 months, but 5% of the drug group had them over 5 years, IR would say both groups have the same risk. But in reality, the drug group had five times more exposure - meaning the event was far less frequent per unit of time. IR hides that.

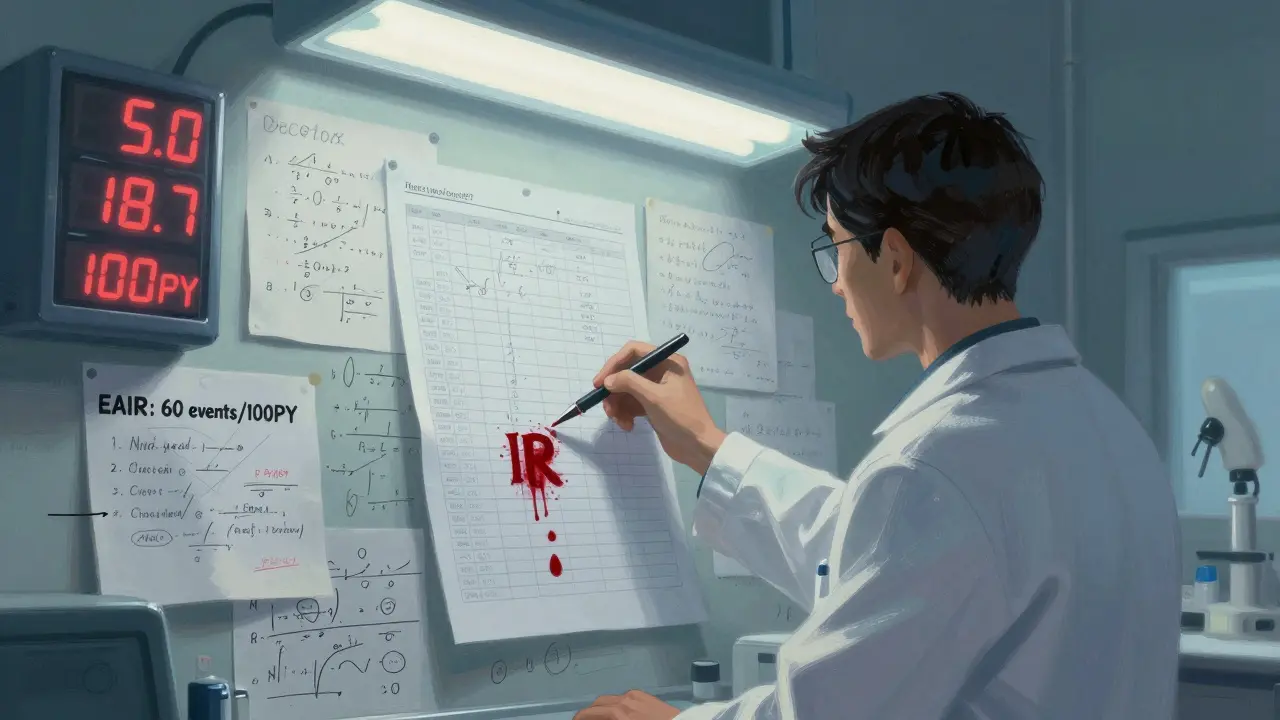

The Shift to Patient-Years: EIR Explained

To fix this, statisticians started using event incidence rate adjusted by patient-years (EIR). Instead of counting people, you count time. One patient-year means one person was exposed for one full year. If 10 people took the drug for 6 months each, that’s 5 patient-years (10 × 0.5). If 3 of them had a rash, the EIR is 3 events per 5 patient-years - or 60 events per 100 patient-years (60/100PY).

This is now standard in tools like JMP Clinical. It answers a better question: "How often does this event happen per year of exposure?" For recurrent events - like diarrhea or dizziness - EIR gives a clearer picture than IR. A drug might cause diarrhea in 20% of people, but if it happens 4 times a year in each person, EIR shows you’re looking at 80 events per 100 patient-years. That’s a very different safety profile than if it happened once and went away.

But EIR has its own blind spot. It counts events, not people. If one person has 10 episodes of vomiting, they count as 10 events. That inflates the rate even if only one person is affected. It’s useful for tracking frequency, but not for knowing how many people are impacted.

The FDA’s New Standard: Exposure-Adjusted Incidence Rate (EAIR)

In 2023, the FDA requested EAIR in a supplemental biologics license application - a clear signal that the industry must move beyond IR and EIR. EAIR doesn’t just count events or people. It accounts for both - and how long each person was actually exposed.

EAIR calculates the number of events divided by total exposure time, but with a twist: it handles interruptions. If a patient stops the drug for 2 weeks due to an unrelated surgery, that time isn’t counted. If they restart, only the time they were actually taking the drug counts. It also adjusts for recurrence - a patient who has 5 episodes over 18 months is treated differently than someone who has one episode and stops.

MSD’s safety team found that switching to EAIR uncovered previously hidden safety signals in 12% of their drug programs - especially in long-term therapies where exposure times varied wildly. A drug for rheumatoid arthritis might show low risk with IR, but EAIR revealed a spike in infections in patients who stayed on treatment beyond 18 months.

That’s why EAIR is becoming the gold standard. The FDA’s 2024 draft guidance proposes standardized methods for calculating it, and CDISC’s latest guidelines now require both IR and EAIR for serious adverse events in oncology trials. The goal? To make safety data reflect real-world use - not just trial math.

Relative Risk: Comparing Safety Between Groups

Once you have your rates - whether IR, EIR, or EAIR - the next step is comparing them. That’s where relative risk comes in. If Drug A has an EAIR of 45 events per 100 patient-years and Drug B has 28, the incidence rate ratio (IRR) is 45 ÷ 28 = 1.6. That means Drug A has a 60% higher rate of the event per year of exposure.

But numbers alone aren’t enough. Confidence intervals tell you if that difference is real or just random noise. The FDA now requires these in submissions. If the 95% confidence interval for the IRR is 1.1 to 2.4, you can be confident the difference is statistically meaningful. If it’s 0.8 to 2.1, you can’t say for sure - the data is too shaky.

Statisticians use the Wald method for IRR confidence intervals. In R, functions like riskratio() handle this automatically. But many teams still make mistakes - 31% of initial analyses have date-handling errors, according to PharmaSUG. A wrong start date, a missing discontinuation record, or an unadjusted holiday period can throw off the whole calculation.

Competing Risks and Why Kaplan-Meier Fails

There’s another layer most people miss: competing risks. What if someone dies before they ever have the adverse event you’re tracking? In cancer trials, death is common. If you use the classic Kaplan-Meier method to estimate time until nausea, you’re assuming everyone stays at risk - even those who died. That overestimates risk.

A 2025 study in Frontiers in Applied Mathematics and Statistics showed that using Kaplan-Meier in these cases leads to inaccurate safety profiles. Instead, researchers now use cumulative hazard ratio estimation. This breaks down risk into separate hazards: one for death, one for the adverse event. It gives a truer picture of how likely an event is, given you’re still alive and on treatment.

Real-World Challenges in Implementation

Even with clear science, putting this into practice is hard. A 2024 PhUSE survey found that SAS programmers spent 3.2 times longer building EAIR analyses than IR ones - 14.7 hours versus 4.5. Common errors? Incorrect event dates (28%), ignoring treatment interruptions (19%), and inconsistent patient-year math (23%).

Roche found that 35% of medical reviewers didn’t understand EAIR at first. They thought a higher number meant worse safety - not realizing it was per year of exposure. Training became mandatory. On the flip side, the PhUSE GitHub repository for standardized EAIR macros has been downloaded over 1,800 times. Teams using it reported an 83% drop in programming errors.

CDISC’s Therapeutic Area User Guide now mandates specific variables for exposure time and event counts. The FDA’s Biostatistics Review Template includes checklists for exposure calculation methods. If you can’t prove how you calculated patient-years, your submission gets flagged.

What This Means for You

If you’re reading a clinical trial summary, don’t just look at "X% had side effects." Ask: Over how long? Was it IR, EIR, or EAIR? If it’s IR, the data might be outdated. If it’s EAIR, you’re seeing a more accurate picture of real-world risk.

For patients, this matters because safety isn’t about whether a side effect happened - it’s about how likely it is to happen while you’re on the drug. A drug with 10% IR might seem safer than one with 15%. But if the first was given for 2 weeks and the second for 2 years, the 15% drug might actually be far safer per day of use.

The industry is moving toward transparency. The global market for clinical safety software hit $1.84 billion in 2023, growing at over 22% a year. More companies are using EAIR. More regulators are demanding it. And more tools are being built to make it easier.

What’s next? By 2027, experts predict 92% of Phase 3 drug submissions will include EAIR. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative is even testing AI tools that auto-detect safety signals using exposure-adjusted data - and early results show a 38% improvement in early warning detection.

Understanding these methods isn’t just for statisticians. It’s for anyone who wants to know what the numbers really mean - and whether a drug’s safety profile is truly understood.

What’s the difference between incidence rate (IR) and exposure-adjusted incidence rate (EAIR)?

IR is the percentage of people who had an adverse event, regardless of how long they were on the drug. EAIR calculates events per unit of exposure time - usually per 100 patient-years - and accounts for how long each person actually took the drug, including interruptions. EAIR gives a more accurate picture of risk over time, especially in long-term trials.

Why did the FDA start requiring EAIR in 2023?

The FDA moved to EAIR because traditional IR methods were misleading in trials with varying treatment durations. Studies showed IR could underestimate true event rates by up to 37% when patients stayed on drugs longer than controls. EAIR accounts for actual exposure time, reducing misinterpretation of safety data and improving risk-benefit assessments.

Is EIR better than IR for all types of adverse events?

EIR is better than IR for recurrent events because it measures frequency per year of exposure. But it overstates risk if one person has many events - it counts events, not people. EAIR improves on EIR by adjusting for both recurrence and variable exposure, making it the most accurate for complex, long-term therapies.

What are competing risks in adverse event analysis?

Competing risks occur when another event - like death - prevents the observation of the adverse event you’re studying. For example, in cancer trials, patients may die before experiencing nausea. Using traditional methods like Kaplan-Meier overestimates risk because it assumes everyone remains at risk. Cumulative hazard ratio estimation separates death risk from adverse event risk to give a more accurate picture.

How do pharmaceutical companies implement EAIR in practice?

Companies use standardized SAS or R code based on CDISC ADaM datasets, with variables for exposure time, treatment start/end dates, and event counts. The PhUSE GitHub repository offers reusable macros that reduce programming errors by 83%. Key steps include validating exposure duration outliers, handling treatment interruptions, and ensuring event dates match protocol records. Training is critical - many reviewers initially misinterpret EAIR as "higher number = worse safety," not realizing it’s normalized per year.

Tom Forwood

February 7, 2026 AT 21:26So basically, if you're on a drug for 5 years and get one headache, that's way less scary than someone who gets 5 headaches in 5 days? Makes sense. I always thought '15% had side effects' was the whole story. Turns out it's like saying '30% of cars have dents' without telling you if it was a parking lot or a highway crash. 😅

Simon Critchley

February 8, 2026 AT 18:09IR is the pharmaceutical industry’s version of ‘trust me bro’ statistics. EIR? Still a band-aid. EAIR? Now we’re talking. You’re not just measuring events-you’re measuring *exposure-time-adjusted biological assault*. If your drug causes 12 vomiting episodes in one patient over 18 months, EAIR says: ‘Hey, that’s 67 events per 100 PY.’ But IR? ‘Oh cool, 1 person puked.’ That’s not safety data-that’s a joke with a FDA stamp. 🤡