Pharmacy Reimbursement Models: How Laws Control Generic Drug Payments

Jan, 15 2026

Jan, 15 2026

When you pick up a generic prescription at the pharmacy, you might assume the price you pay is straightforward. But behind that $4.50 copay or $12 out-of-pocket cost is a tangled web of federal and state laws, payment formulas, and corporate contracts that decide exactly how much the pharmacy gets paid-and whether they lose money on the deal. This isn’t just about pharmacy profits. It’s about whether you can afford your meds, whether your pharmacist can tell you a cheaper option exists, and why some generics suddenly disappear from shelves.

How Generic Drugs Get Paid For

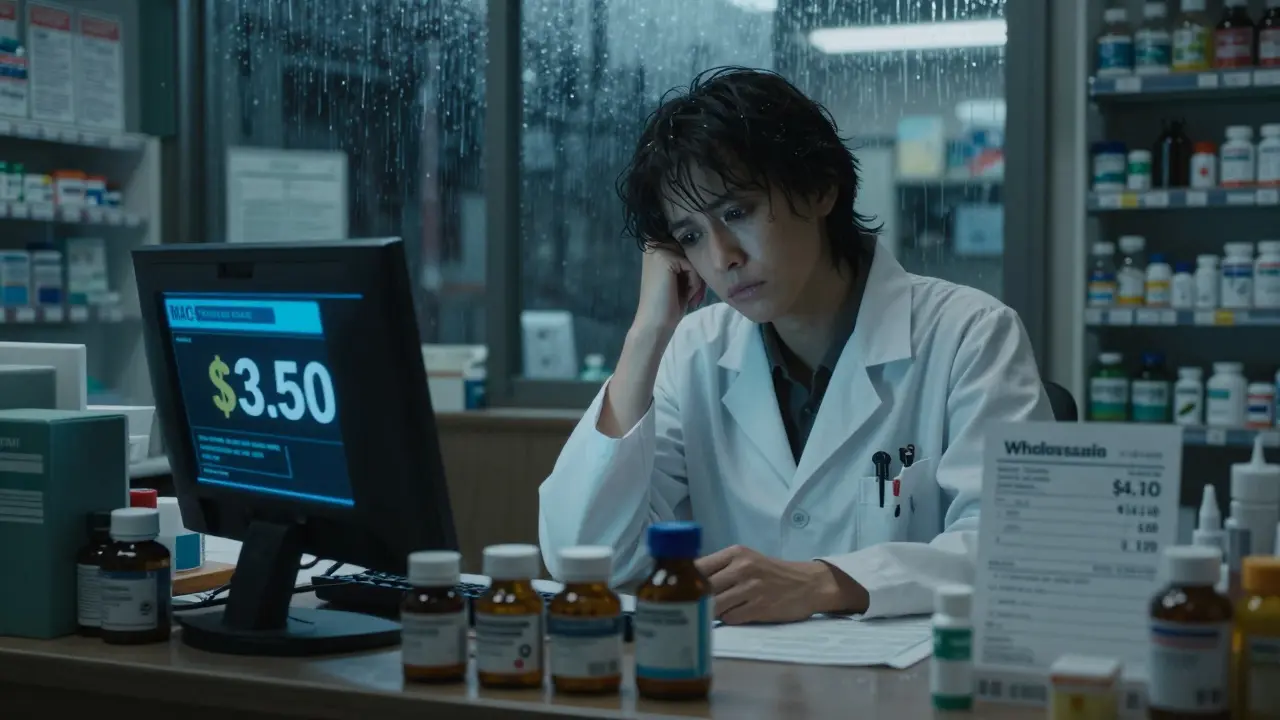

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they only account for 23% of total drug spending. That’s the whole point: they’re cheaper. But how much cheaper, and who gets paid what, depends on the reimbursement model used. There are two main ways pharmacies get reimbursed for generics: Average Wholesale Price (AWP) and Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC). AWP is a list price set by manufacturers, often inflated and not reflective of what pharmacies actually pay. Many plans used to reimburse based on AWP minus a percentage-say, AWP minus 20%. But because AWP is unreliable, most public and private plans have moved to MAC programs. MAC is the real-world cost cap. It’s the maximum amount a plan will pay for a specific generic drug, based on what pharmacies are actually paying wholesalers. If the pharmacy buys a 30-day supply of lisinopril for $3.20, and the MAC is set at $3.50, they get $3.50. If they paid $4.10 for it? They eat the $0.60 loss. That’s why independent pharmacies often operate on razor-thin margins-sometimes just 1.4% profit per generic script in 2023, down from 3.2% in 2018.The Role of Laws: From Hatch-Waxman to GDUFA

The modern generic drug system was built by two major laws. The first, the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, let generic manufacturers skip expensive clinical trials by proving their drug is bioequivalent to the brand. In return, they had to respect brand patents. This created a race to be first to file-and first to profit. The second, the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), reauthorized in 2017, changed how the FDA reviews generics. Before, all generic companies paid the same flat fee, no matter how many drugs they made. Big players could afford it. Small ones couldn’t. GDUFA II introduced tiered fees based on portfolio size. That helped smaller companies enter the market, increasing competition and driving prices down. But laws don’t just encourage generics-they also restrict them. Authorized generics are a loophole. Brand companies sometimes release their own generic version, sold under a different label, right when the first generic hits the market. This blocks other generics from entering, because the market is already filled. One study found this practice delayed competition for up to 18 months in some cases.Who Controls the Money: PBMs and the Spread

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) like CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRX handle 80% of all prescription claims in the U.S. They don’t just process claims-they negotiate rebates, set formularies, and decide reimbursement rates. One of the most controversial practices is spread pricing. Here’s how it works: your insurance plan agrees to pay the PBM $15 for a generic drug. The PBM tells the pharmacy it will pay $12. The pharmacy dispenses the drug and gets $12. The PBM pockets the $3 difference-the “spread.” That $3 isn’t passed on to you or your insurer. It’s pure profit for the PBM. Until 2018, PBMs also used gag clauses to prevent pharmacists from telling you that paying cash for the same drug might cost less than your copay. A 2019 study found 1 in 5 prescriptions were affected. Those clauses are now banned in all 50 states, but the spread still exists-and it’s hidden.

Medicare Part D and the Drug List

Medicare Part D covers 50.5 million people. In 2022, generics made up 84% of prescriptions but only 27% of spending. Why? Because even though the drugs are cheap, formulary rules and cost-sharing structures make them expensive for patients. Most Part D plans have tiered copays: $5 for generics, $40 for brands, $80+ for non-preferred drugs. But many plans also require prior authorization for generics-meaning your doctor has to jump through hoops just to get you the cheapest option. In 2022, 28% of Part D plans required prior auth for at least one generic drug. In 2025, CMS is testing a new model: the $2 Drug List. It’s simple: select about 100-150 low-cost, high-use generics (like metformin, levothyroxine, or atorvastatin) and cap the patient copay at $2, no matter your plan. The goal? Improve adherence, cut out confusing tiers, and stop patients from skipping meds because they can’t afford the copay-even if the drug costs $1.20. This model is inspired by Walmart and Kroger, which already offer $4 generic lists. But Medicare’s version will be standardized across all Part D plans that opt in. If it works, it could become permanent.State Laws and Medicaid’s Hidden Rules

Medicaid covers 85 million people-and each state runs its own program. Most use Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs), where the state’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee picks which generics are preferred (cheaper copay) and which aren’t (higher copay or require prior auth). As of 2023, 44 states have passed laws to regulate PBMs. These laws require transparency in reimbursement rates, ban spread pricing in Medicaid, and mandate that pharmacies be paid at least the actual acquisition cost of the drug. Some states, like California and New York, now require PBMs to pass rebates directly to consumers instead of keeping them. But enforcement is patchy. Independent pharmacies still struggle. One pharmacist in Ohio told a reporter she lost $1.80 on every 30-day supply of metformin because the MAC rate hadn’t been updated in 14 months-even though the drug’s wholesale price dropped 40%.

Stephen Tulloch

January 16, 2026 AT 15:49Melodie Lesesne

January 17, 2026 AT 11:08Corey Sawchuk

January 17, 2026 AT 17:51Joie Cregin

January 18, 2026 AT 00:17Riya Katyal

January 19, 2026 AT 07:14waneta rozwan

January 20, 2026 AT 07:35Nicholas Gabriel

January 22, 2026 AT 00:16swarnima singh

January 23, 2026 AT 19:19