Medical Society Guidelines on Generic Drug Use: What Providers Really Think

Nov, 25 2025

Nov, 25 2025

When a pharmacist hands you a pill bottle with a different name than what your doctor wrote, you might wonder: is this the same drug? For many patients, it is. But for some, it’s not that simple. Medical societies - the groups that set standards for how doctors practice - have taken official, often conflicting, stances on when generic drugs can be swapped in place of brand-name ones. These aren’t just bureaucratic rules. They’re life-or-death decisions for people with epilepsy, cancer, or heart conditions.

Why Generic Drugs Are Everywhere (And Why It Matters)

Nearly 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generic drugs. Yet they make up only about 23% of total drug spending. That’s not a fluke. It’s by design. The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act created a fast-track approval system for generics, requiring them to prove they deliver the same active ingredient, in the same strength and form, as the brand-name version. The FDA says they’re bioequivalent - meaning their blood levels fall within an 80% to 125% range of the original. For most drugs, that’s plenty close enough. But here’s the catch: bioequivalence doesn’t always mean therapeutic equivalence. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI), even tiny differences in absorption can push a patient from safe to toxic, or from controlled to seizing. That’s why some medical societies draw a hard line.The Neurology Stand: No Substitutions for Seizure Drugs

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) is one of the clearest voices against automatic generic substitution. Their official position, updated in 2023, says: do not substitute generic anticonvulsants without the prescriber’s explicit approval. Why? Because epilepsy isn’t like high blood pressure. A 5% drop in blood levels of levetiracetam or phenytoin might not show up on a lab test - but it could trigger a breakthrough seizure. One survey of neurologists found that 68% believe generic switches have led to worsening control in their patients. That’s not speculation. It’s clinical experience. The AAN’s stance isn’t about distrust in generics. It’s about precision. For drugs where the margin between effective and dangerous is razor-thin, consistency matters more than cost. That’s why only a handful of states allow automatic substitution for NTI drugs - and even then, only with the doctor’s consent.General Medicine Says: Swap Away

Meanwhile, the American College of Physicians (ACP) and other broad-based groups take a different view. They support generic substitution for nearly all drug classes - antibiotics, statins, blood pressure meds, even some diabetes drugs. Their reasoning? The FDA’s approval process works. If a generic passes bioequivalence testing, it’s safe to use. Real-world data backs them up. For drugs like atorvastatin or metformin, switching to generic versions has led to no increase in hospitalizations or side effects. Millions of patients have made the switch without issue. For these conditions, the cost savings are massive - and the clinical risk is low. The key difference? Therapeutic index. If a drug has a wide safety margin, the small variations allowed under FDA rules don’t matter. But if it doesn’t - like with warfarin, lithium, or certain seizure meds - then the rules change.

Oncology’s Hidden Rule: Off-Label Generics Are Okay

Here’s where things get surprising. In cancer care, off-label use of generics is common - and accepted. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines, used by most U.S. oncologists, list dozens of generic drugs used for conditions they weren’t originally approved for. A generic chemotherapy drug approved for lung cancer might be used off-label for breast cancer - and it’s still covered by Medicare. Why? Because the NCCN treats these drugs as interchangeable based on biological similarity, not just FDA labels. If two drugs have the same active ingredient and similar pharmacokinetics, they’re considered therapeutically equivalent - even if the brand-name version was never tested for that specific cancer type. This creates a unique system: generics aren’t just cheaper alternatives. They’re the backbone of modern cancer treatment. About 42% of cancer drug uses in NCCN guidelines are off-label, and nearly all of them involve generics.The Naming Game: How Generic Names Keep Patients Safe

You’ve probably noticed that generic names look weird. Carvedilol, metoprolol, lamotrigine. They’re not random. They’re built on a system created by the American Medical Association’s United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council. The council’s job is to give every drug a name that tells doctors what it does - and avoids confusion. For example, drugs ending in “-lol” are beta-blockers. Those ending in “-pril” are ACE inhibitors. This helps prevent errors when writing prescriptions or reading labels. The USAN Council won’t approve a name if it sounds too similar to another drug. They avoid prefixes that could be mistaken for “Zoloft” or “Lipitor.” Why? Because a misread name can lead to a wrong drug - and that’s deadly. This naming system isn’t just about branding. It’s a safety tool. And it’s one reason why many doctors feel more confident prescribing generics - they can tell at a glance what class the drug belongs to.

The Real Conflict: State Laws vs. Medical Advice

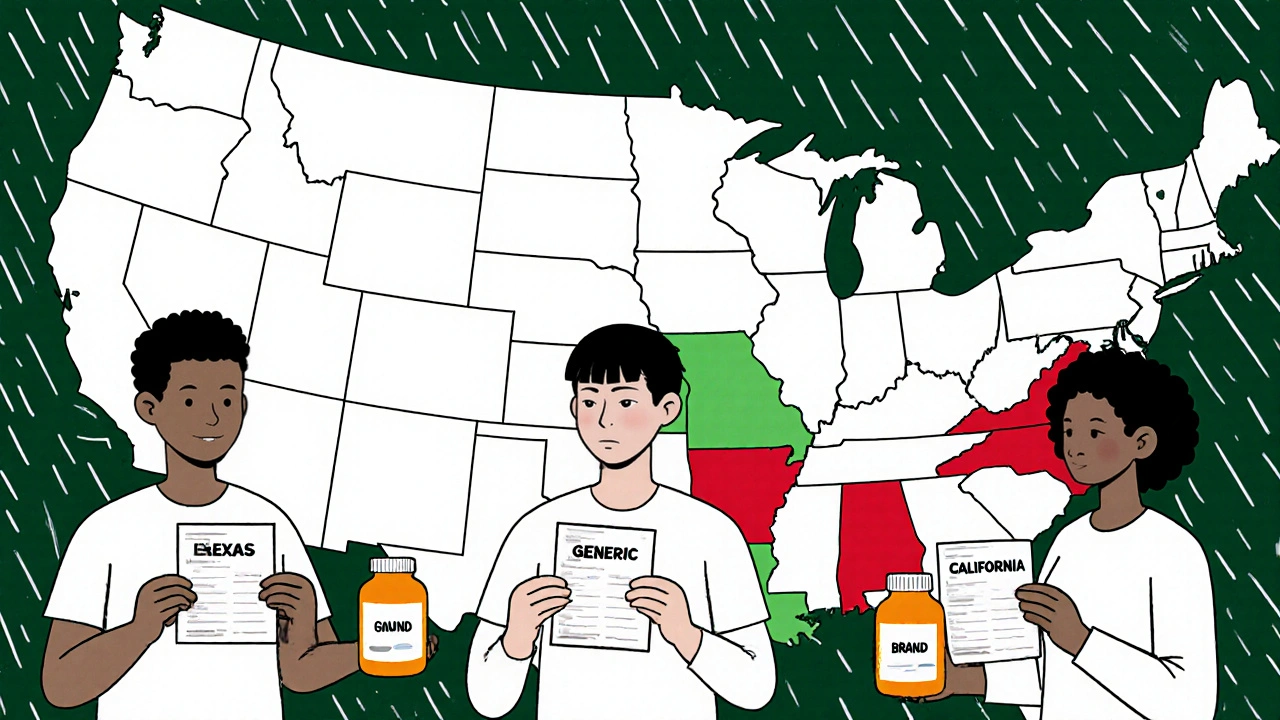

Here’s where things get messy in practice. State laws often force pharmacists to substitute generics unless the doctor writes “dispense as written” or “no substitution.” But those laws don’t always match what medical societies recommend. A pharmacist in Texas might be legally required to swap a generic for a brand-name seizure drug - even if the neurologist says not to. The doctor’s note might be ignored. The patient gets the wrong version. No one realizes until they have a seizure. Some states have passed laws that block automatic substitution for NTI drugs. Others haven’t. That means two patients with identical prescriptions could get different treatments based on where they live. Doctors don’t always know what’s happening at the pharmacy. And patients rarely speak up - they assume the pharmacist knows best.What Providers Need to Do

If you’re a prescriber, here’s what you need to do right now:- Know your drug’s therapeutic index. If it’s NTI - like warfarin, levetiracetam, or cyclosporine - write “dispense as written” on the prescription.

- Check your specialty society’s guidelines. Don’t assume all generics are equal. Neurology, psychiatry, and transplant medicine have stricter rules.

- Talk to your patients. Ask: “Have you ever switched to a generic version of this drug? Did you notice any changes?” Many patients won’t volunteer this unless asked.

- Know your state’s substitution laws. Some require written consent for NTI drugs. Others don’t. Your liability changes depending on where you practice.

What’s Next?

The FDA continues to update its Orange Book, which lists which generics are rated as therapeutically equivalent. Medical societies are slowly aligning with these ratings - but they’re not abandoning their specialty-specific warnings. The future likely holds more clarity: electronic prescribing systems may soon flag NTI drugs and block automatic substitution unless overridden by the prescriber. But until then, the burden falls on the doctor to know the rules - and speak up when they matter. Generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system billions. But they’re not one-size-fits-all. For some patients, the difference between brand and generic isn’t about cost. It’s about survival.Are generic drugs always safe to substitute for brand-name drugs?

No. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) - like anticonvulsants, warfarin, lithium, or cyclosporine - even small differences in absorption can cause serious harm. Medical societies like the American Academy of Neurology explicitly oppose automatic substitution for these drugs. For most other medications, generics are considered safe and effective.

Why do some doctors refuse to allow generic substitution?

Doctors who refuse substitution usually treat patients with conditions where precision matters most - epilepsy, transplant rejection, or severe mental illness. In these cases, a small drop in drug levels can lead to breakthrough seizures, organ rejection, or relapse. Clinical experience shows that switching generics can trigger adverse events, even when the FDA says the drugs are bioequivalent.

Can pharmacists substitute generics without the doctor’s permission?

It depends on state law. In most states, pharmacists can substitute generics unless the prescription says “dispense as written” or “no substitution.” But for NTI drugs, some states require the prescriber’s consent before substitution. Many doctors aren’t aware of these laws, and patients often don’t know to ask.

Do generic cancer drugs work the same as brand-name ones?

Yes - and that’s why they’re widely used in oncology. The NCCN Guidelines accept generic chemotherapy drugs for off-label uses, as long as they’re therapeutically equivalent. Many cancer treatments rely on generics because they’re affordable and proven safe. The key is that these drugs are used based on biological similarity, not just FDA-approved labels.

How are generic drug names chosen, and why does it matter?

The American Medical Association’s USAN Council assigns generic names using standardized stems (like “-pril” for ACE inhibitors) to help doctors quickly identify drug classes. Names are designed to avoid confusion with similar-sounding drugs. This reduces prescribing and dispensing errors - making generics safer to use in practice.

mohit passi

November 27, 2025 AT 09:53Genetics aren't magic ✨ but they're damn close when it comes to saving lives. I've seen grandparents in Delhi on generics for hypertension-no issues, no seizures, just cheaper meds and more rice on the table. Cost isn't just a number-it's dignity. 🌏💊

Aaron Whong

November 28, 2025 AT 16:17From a pharmacoeconomic standpoint, the bioequivalence paradigm-while statistically robust-is fundamentally reductionist when applied to NTI pharmacodynamics. The FDA’s 80–125% AUC/Cmax window is a regulatory artifact, not a clinical guarantee. We’re conflating statistical equivalence with therapeutic homogeneity-a category error with mortal consequences.

Especially in transplant recipients on cyclosporine: a 10% fluctuation in trough levels isn't noise-it's rejection. The AAN’s stance isn't Luddite; it's precision medicine in its purest form.

Sanjay Menon

November 30, 2025 AT 12:53Oh, so now we’re treating epilepsy like it’s some sacred rite? 🙄 The AAN has been clinging to this myth since the 90s. Meanwhile, Europe swaps generics daily and doesn’t have a national epilepsy crisis. It’s not that they’re smarter-they’re just not obsessed with branding.

And don’t get me started on the US pharmacy system. It’s a circus run by accountants in lab coats.

Cynthia Springer

December 1, 2025 AT 13:33I’ve been on lamotrigine for 12 years. Switched to generic twice. First time-mild dizziness for a week. Second time-nothing. My neurologist said it’s fine if I monitor. I do. I track my sleep, mood, seizures in a journal. Maybe the real issue isn’t the generic-it’s that we don’t teach patients how to self-monitor?

Brittany Medley

December 1, 2025 AT 21:46For anyone reading this: if you’re on warfarin, lithium, levetiracetam, or cyclosporine-DO NOT let your pharmacist switch your med without checking with your doctor first. Write "DO NOT SUBSTITUTE" in big letters on the prescription. Even if the script says "dispense as written," pharmacists sometimes overlook it. I’ve seen it happen. It’s not paranoia-it’s protection. 🛡️

Also, ask for the generic manufacturer name. Some brands are more consistent than others. You deserve to know what’s in your bottle.

Marissa Coratti

December 3, 2025 AT 12:50It is of paramount importance to recognize that the regulatory framework established by the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, while revolutionary in its intent to reduce pharmaceutical expenditures, has inadvertently created a structural vulnerability in the delivery of care for patients requiring pharmacokinetic stability. The notion that bioequivalence-defined by a statistical confidence interval-is synonymous with clinical equivalence is, frankly, a dangerous oversimplification. In oncology, where off-label use of generics is not only accepted but actively encouraged by the NCCN, we are witnessing a paradigm shift in therapeutic accessibility-but this shift must be accompanied by rigorous pharmacovigilance, longitudinal patient tracking, and prescriber education. Without these safeguards, we risk commodifying life-saving interventions, reducing complex human physiology to a cost-per-dose metric.

Rachel Whip

December 5, 2025 AT 04:41Just wanted to add-when I worked in a community pharmacy, I saw patients on levetiracetam switch to generic and come back saying, ‘I feel weird.’ We didn’t know why until the neurologist called and said, ‘Don’t switch that one.’ Now I always check the NTI list before dispensing. It’s not about trust-it’s about knowing the rules. And yes, some states are better than others. Texas? Not so much.

james thomas

December 6, 2025 AT 11:26Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know this, but generics are basically knockoffs. The FDA lets them slide because they’re bribed. Why do you think the brand-name seizure meds cost $500 a month? So they can keep you hooked. The ‘bioequivalent’ claim? Marketing. My cousin’s kid had a seizure after switching. The pharmacy didn’t even tell us. 😡

Deborah Williams

December 6, 2025 AT 19:53Interesting how the same people who scream about ‘big pharma greed’ when brand names are expensive suddenly become terrified of generics when it’s their kid’s brain on the line. 🤷♀️ It’s not the drug-it’s the fear of losing control. We treat epilepsy like it’s witchcraft, not medicine. Meanwhile, in Japan and Germany, they swap generics like socks and no one’s dropping dead.

Maybe the real problem isn’t the pill-it’s the cultural obsession with brand as safety. We need to grow up.

Kaushik Das

December 6, 2025 AT 21:55Back home in Mumbai, we’ve been using generics for decades-no drama, no lawsuits. My uncle took generic phenytoin for 20 years, never had a seizure. The real issue? Access. If you can’t afford the brand, you don’t get treated. So we use generics. And we survive. Maybe the US needs to stop over-engineering safety and start fixing affordability.

Also, love the USAN naming system. ‘-pril’ for ACE inhibitors? Genius. Makes me feel like I’m reading a secret code. 🧠

Asia Roveda

December 7, 2025 AT 15:00Let’s be real: this whole generic debate is just woke medicine. You want to save money? Fine. But don’t pretend your ‘personalized’ neurology concerns are science. It’s just fear-mongering wrapped in a white coat. America spends more on healthcare than every other country combined-and we’re still acting like we’re broke. Fix the system. Don’t hide behind NTI myths.