How Insurer-Pharmacy Negotiations Set Generic Drug Prices

Feb, 7 2026

Feb, 7 2026

Ever filled a prescription for a generic drug and been shocked by the price? You’re not alone. Many people think insurance should make drugs cheaper. But in reality, the system often makes them more expensive - especially for generics. The reason? It’s not about the drug itself. It’s about how insurers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), and pharmacies negotiate prices behind closed doors.

Who’s Really Setting the Price?

You might assume your insurance company directly talks to drug makers to set prices. It doesn’t. The real negotiators are Pharmacy Benefit Managers - or PBMs. These are middlemen hired by insurers to manage drug benefits. Think of them as the hidden power players in your prescription drug costs. They decide which drugs are covered, what your copay is, and how much pharmacies get paid when they fill your prescription.Three companies - OptumRx, CVS Caremark, and Express Scripts - control about 80% of the PBM market. That kind of concentration means they hold enormous leverage. They don’t just negotiate with drugmakers. They negotiate with pharmacies too. And they do it in ways most people never see.

The Hidden Math: How Generic Prices Are Calculated

Generic drugs are supposed to be cheap. After all, they’re copies of brand-name drugs with no research costs. But how much you pay at the pharmacy depends on a tangled web of formulas. PBMs use two main benchmarks to set reimbursement rates:- Average Wholesale Price (AWP): A list price set by manufacturers, often inflated and not reflective of real market value.

- National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC): A government-calculated average of what pharmacies actually pay for drugs.

PBMs typically reimburse pharmacies based on NADAC plus a small dispensing fee - say $3 to $5. But here’s where it gets strange. When you, the patient, go to pay your copay, the amount you’re charged is based on a different number: the PBM’s negotiated rate with your insurer. That rate? It’s often much higher than what the pharmacy paid.

This gap is called spread pricing. PBMs charge your insurer $45 for a generic drug, reimburse the pharmacy $12, and pocket the $33 difference. You’re not seeing this. Your insurance card doesn’t show it. Your receipt doesn’t mention it. But you’re paying for it - through higher premiums, higher copays, or both.

Why Your Insurance Might Cost More Than Cash

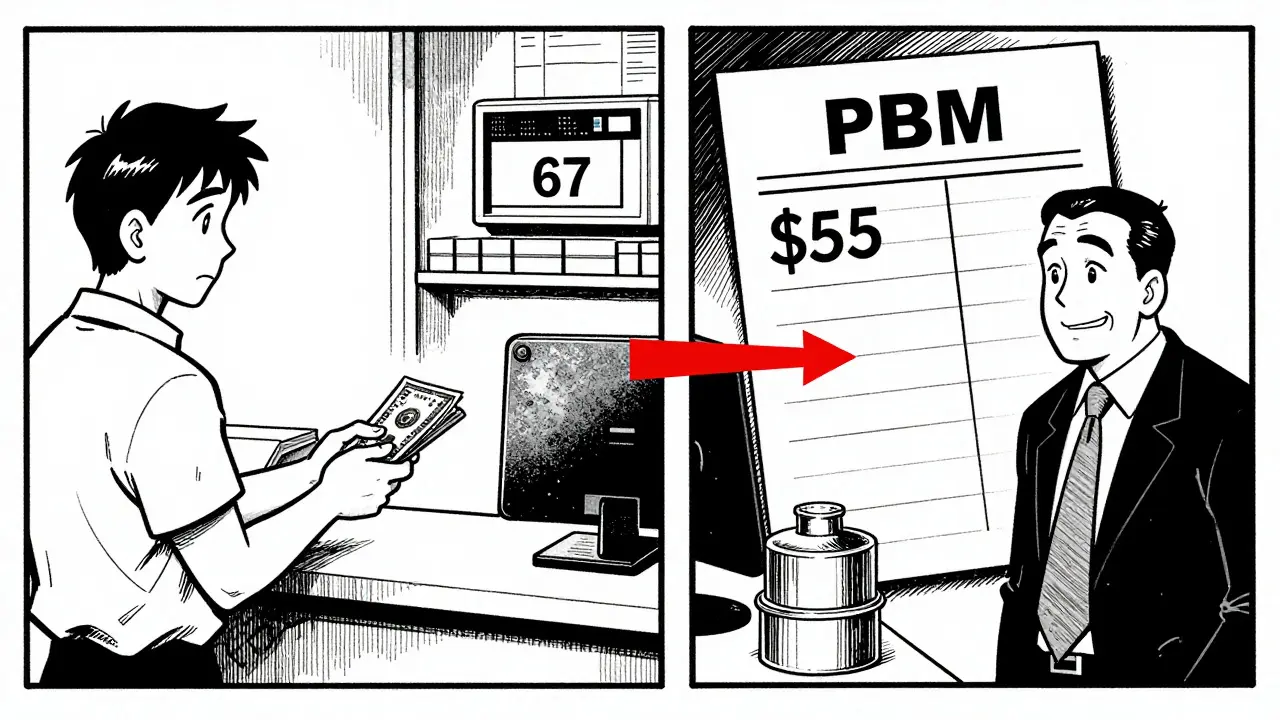

Here’s the kicker: in many cases, paying cash for a generic drug is cheaper than using your insurance.A 2023 Wall Street Journal investigation found patients on insurance sometimes paid three to ten times more than the cash price. One man paid $45 for a generic version of a multiple sclerosis drug through his plan. At the same pharmacy, the cash price was $4. Another woman paid $67 for a generic heart medication. The cash price? $11.

Why does this happen? Because PBMs structure copays as fixed amounts - $5, $10, $25 - regardless of the actual drug cost. If the PBM’s negotiated price is $50, your $10 copay stays $10. The rest gets billed to your insurer. But if the real cost of the drug is only $12, the PBM still collects $38 in spread. You’re stuck paying your fixed copay while the PBM profits from the gap.

That’s why 42% of insured adults in a 2024 Consumer Reports survey reported paying more out-of-pocket for a generic than they would have if they’d paid cash. And 28% said it happened to them more than once a year.

The Gag Rule: Pharmacists Can’t Tell You the Truth

You’d think your pharmacist could just say, “Hey, this drug is cheaper if you pay cash.” But most can’t. Over 90% of PBM contracts include “gag clauses” that legally prevent pharmacists from informing patients about lower cash prices. These clauses were so widespread that Congress banned them in 2020 - but enforcement is weak. Many PBMs still find ways to silence pharmacists through contract penalties or threats to cut off network access.Without this transparency, patients have no way to compare. They assume insurance always saves money. It doesn’t - not always. Not for generics.

Who Pays the Real Cost?

The damage isn’t just to patients. Independent pharmacies are being squeezed out. PBMs force them into narrow networks with low reimbursement rates. Many pharmacies can’t afford to fill prescriptions at a loss. So they either close or stop offering generics altogether.Between 2018 and 2023, over 11,300 independent pharmacies shut down. Why? Because PBMs don’t just set low prices - they claw them back. A pharmacy fills a prescription, gets paid, then weeks later, the PBM says, “Oops, we miscalculated. We’re taking back $8.” This is called a “clawback.” It affects 63% of independent pharmacies, according to FTC data from 2023.

Pharmacists now spend 200 to 300 hours a year just trying to understand PBM contracts. Some hire specialists for $100,000 a year just to decode the mess. Small pharmacies can’t afford that. Big chains? They have legal teams. Independent pharmacies? They’re left scrambling.

The Bigger Picture: Billion in Hidden Profits

The PBM system isn’t broken - it’s designed this way. Evaluate Pharma estimated in 2024 that spread pricing generates $15.2 billion annually in undisclosed revenue, with 68% of that coming from generic drugs. That’s not profit from efficiency. That’s profit from opacity.And here’s the irony: the more expensive a drug’s list price is, the bigger the rebate the PBM gets from the manufacturer. So PBMs have an incentive to push higher-priced drugs - even if cheaper generics exist. The system rewards high list prices, not low costs.

Dr. Joseph Dieleman of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation put it bluntly: “Higher list prices generate larger rebates - and higher out-of-pocket costs for patients.”

What’s Changing?

Pressure is building. In September 2024, the Biden administration issued an executive order banning spread pricing in federal programs - effective January 2026. Forty-two states are now passing laws requiring PBMs to disclose their fees and pricing practices. The Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program, launched under the Inflation Reduction Act, is starting to influence private markets. If the government can negotiate lower prices for Medicare, why not for everyone?Legislation like the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Transparency Act of 2025 would force PBMs to pass 100% of rebates to insurers - meaning savings would go back to plan sponsors, not into PBM pockets.

But don’t expect quick fixes. The industry is fighting back. Drugmakers warn that lowering PBM profits will hurt innovation. But the numbers don’t lie: generics make up 90% of prescriptions but only 23% of total drug spending. The money isn’t disappearing into research. It’s disappearing into spreads, clawbacks, and secret contracts.

What You Can Do

You can’t change the system overnight. But you can protect yourself:- Always ask the pharmacist: “What’s the cash price?”

- Use apps like GoodRx or SingleCare to compare prices before you fill.

- If your copay is higher than the cash price, pay cash and submit a claim for reimbursement if your plan allows it.

- Check if your employer offers a transparent pharmacy benefit - only 12% of plans do, but they exist.

Generic drugs are meant to save money. Right now, they’re being used to make money - for companies you’ve never heard of. And you’re the one paying for it.