Cmax and AUC in Bioequivalence: What Peak Concentration and Total Exposure Really Mean

Dec, 20 2025

Dec, 20 2025

When a generic drug hits the market, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it will work the same way in your body? The answer lies in two simple but powerful numbers: Cmax and AUC. These aren’t just lab terms-they’re the foundation of whether a generic drug is safe and effective for you.

What Cmax and AUC Actually Measure

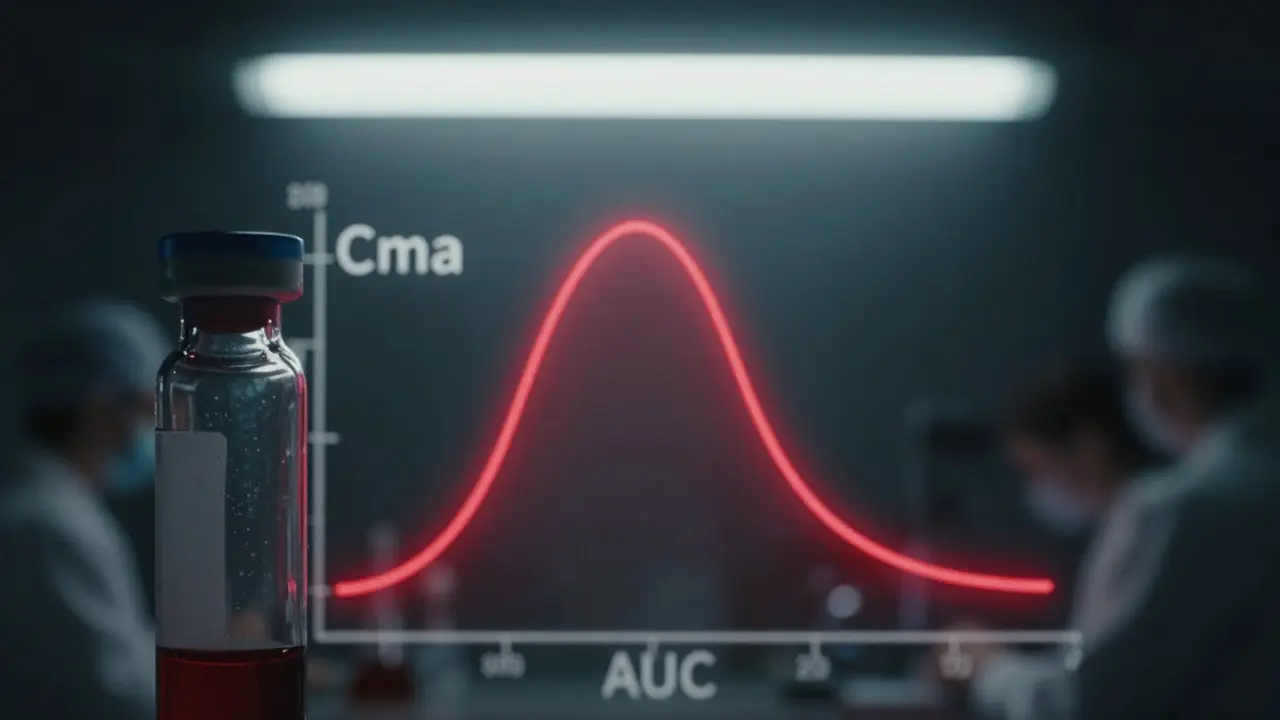

Cmax stands for maximum concentration. It tells you the highest level of a drug that reaches your bloodstream after you take it. Think of it like the peak of a wave-the highest point before it starts to drop. If you take a painkiller and feel relief within 30 minutes, that’s your Cmax kicking in.

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total exposure. It’s not just about the peak-it’s about how much drug your body is exposed to over time. Imagine a graph where time is on the bottom and drug concentration is on the side. AUC is the space under that curve. A higher AUC means your body has absorbed more of the drug over hours or days.

Here’s why both matter: Cmax tells you how fast the drug works. AUC tells you how much it works. For some drugs, like antibiotics or blood thinners, getting the right amount over time is more important than how fast it hits peak. For others, like fast-acting painkillers or seizure meds, hitting the right peak quickly is critical to avoid side effects or breakthrough symptoms.

Why Both Are Required-Not Just One

Regulators don’t just check one number. They require both Cmax and AUC to pass the same test. Why? Because a drug could have the same total exposure (AUC) but spike too high or too low at the peak (Cmax), and that’s dangerous.

Take warfarin, a blood thinner. If a generic version causes a sudden spike in concentration-even if the total exposure is identical-it could lead to dangerous bleeding. On the flip side, if the peak is too low, it might not prevent clots. That’s why the FDA and EMA demand both metrics meet strict criteria.

Studies show that when only one parameter passes, the drug is rejected. In fact, industry data reveals that about 15% of bioequivalence studies fail because sampling was too sparse during the absorption phase, leading to inaccurate Cmax values. That’s why studies collect blood samples every 15 to 30 minutes in the first few hours-missing even one key time point can throw off the whole result.

The 80%-125% Rule: How Bioequivalence Is Proven

The standard for approval is simple: the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of generic to brand-name drug must fall between 80% and 125% for both AUC and Cmax. That means if the brand-name drug gives you an AUC of 100 units, the generic must deliver between 80 and 125 units. Same for Cmax.

This range didn’t come out of nowhere. It was chosen in the early 1990s based on decades of clinical data showing that differences smaller than 20% rarely affect how a drug works in real patients. The math behind it uses logarithmic transformation because drug concentrations in blood don’t follow a normal bell curve-they follow a log-normal pattern. That’s why statisticians log-transform the data before comparing it.

There are exceptions. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like lithium, digoxin, or levothyroxine-regulators sometimes tighten the range to 90%-111%. Why? Because even a 10% difference can cause toxicity or treatment failure. The EMA has formalized this for certain drugs, and the FDA is moving toward similar rules for others.

How Studies Are Done-And Why They’re So Precise

Bioequivalence studies aren’t done in patients. They’re done in healthy volunteers-usually 24 to 36 people. Each person takes both the brand and generic versions, at different times, in a crossover design. This removes individual differences in metabolism from the equation.

Blood is drawn 12 to 18 times over 24 to 72 hours, depending on the drug’s half-life. For fast-acting drugs, samples are taken every 15 minutes in the first hour. For slow-release versions, sampling might stretch over several days. The equipment? Highly sensitive mass spectrometers that can detect drug levels as low as 0.1 nanograms per milliliter.

It’s not just about accuracy-it’s about timing. The EMA’s guidelines stress that actual sampling times must be used, not scheduled ones. If a blood draw was supposed to be at 2 hours but happened at 2 hours and 12 minutes, that 12-minute difference gets factored into the calculation. This level of detail is why bioequivalence studies cost tens of thousands of dollars per drug.

What Happens When the Numbers Don’t Match

Not every generic passes. If Cmax or AUC falls outside the 80%-125% range, the application is rejected. Companies don’t get a second chance without redesigning the formulation-changing fillers, coating, or particle size. Sometimes, they have to re-run the entire study.

One common failure point? Poor sampling during absorption. If you don’t capture the true peak, Cmax looks lower than it really is. That can make a perfectly good generic look like it’s underperforming. Industry reports show that about 15% of study failures are due to inadequate sampling schedules.

Another issue? High variability. Some drugs behave wildly differently from person to person. For those, the standard 80%-125% rule can be too strict. The EMA allows “scaled bioequivalence” for these cases, letting the range widen based on how much the drug varies between individuals. The FDA has similar rules, but they’re harder to qualify for.

Real-World Impact: Are Generics Really the Same?

Here’s the bottom line: over 1,200 generic drugs were approved in the U.S. in 2022 alone-and nearly all of them passed the Cmax and AUC test. A 2019 review of 42 studies published in JAMA Internal Medicine found no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness between brand-name and generic drugs that met bioequivalence standards.

Patients who switch from brand to generic for conditions like epilepsy, hypertension, or depression rarely report changes in how they feel. That’s not luck-it’s science. The Cmax and AUC criteria have been validated over 40 years of clinical use. They’re not perfect, but they’re the best tool we have to ensure that a $5 pill works like a $50 one.

The Future: Are Cmax and AUC Still Enough?

Some scientists are asking if we need more than just these two numbers. For complex drugs-like extended-release tablets that release medicine in two waves, or inhalers that deliver drug to the lungs-Cmax and AUC might not capture the full picture.

The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance suggests looking at partial AUC (like exposure in the first 4 hours) for these cases. The EMA is also exploring new metrics for narrow therapeutic index drugs. But even with these advances, Cmax and AUC remain the gold standard for 95% of all generic drugs.

As Dr. Robert Lionberger of the FDA said in 2022: “AUC and Cmax will remain the primary bioequivalence endpoints for conventional drug products for the foreseeable future.” Why? Because they’ve been tested, proven, and trusted across millions of patients. They’re simple, measurable, and directly tied to how drugs work in the body.

So next time you pick up a generic pill, remember: it didn’t just get approved because it’s cheaper. It passed a rigorous, science-backed test that ensures it delivers the same peak and the same total exposure as the original. That’s not marketing. That’s medicine.

What does Cmax mean in bioequivalence?

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration-the highest level a drug reaches in your bloodstream after you take it. It tells you how quickly the drug is absorbed. For fast-acting medicines like painkillers, Cmax determines how soon you feel relief. Regulators require Cmax to fall within 80%-125% of the brand-name drug’s value to ensure the generic works at the same rate.

What does AUC mean in bioequivalence?

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total drug exposure over time. It’s calculated by plotting drug concentration in your blood against time and measuring the space under that curve. AUC tells you how much of the drug your body has absorbed overall. For drugs that need steady levels-like blood pressure or seizure meds-AUC is more important than Cmax. To be bioequivalent, the generic’s AUC must be within 80%-125% of the brand-name drug.

Why do both Cmax and AUC need to pass for bioequivalence?

Because they measure different things. Cmax tells you how fast the drug enters your system. AUC tells you how much you’re exposed to over time. A drug could have the same total exposure (AUC) but spike too high or too low at the peak (Cmax), leading to side effects or lack of effectiveness. Regulatory agencies require both to pass because missing one could mean the generic behaves differently in your body-even if the overall dose looks the same.

What is the 80%-125% rule for bioequivalence?

The 80%-125% rule means that the ratio of the generic drug’s AUC or Cmax to the brand-name drug’s value must fall within that range when analyzed statistically. This range was chosen because studies show differences smaller than 20% are unlikely to affect how well a drug works or its safety. The numbers are log-transformed before analysis because drug concentrations follow a log-normal distribution, not a normal one.

Are there drugs that need stricter bioequivalence limits?

Yes. Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-where small changes in dose can cause serious harm-require tighter limits. For drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, or lithium, regulators sometimes require the ratio to fall within 90%-111%. This is because even a 10% difference in exposure can lead to toxicity or treatment failure. The EMA has formalized these tighter limits for specific drugs, and the FDA is moving toward similar rules.

How do scientists measure Cmax and AUC?

In bioequivalence studies, healthy volunteers take both the brand and generic drug in a crossover design. Blood samples are drawn every 15-30 minutes in the first few hours, then less frequently over 24-72 hours. Drug levels are measured using highly sensitive machines called LC-MS/MS, which can detect concentrations as low as 0.1 nanograms per milliliter. Cmax is the highest measured value. AUC is calculated using the trapezoidal rule to estimate the area under the concentration-time curve.

Why are bioequivalence studies done in healthy volunteers, not patients?

Healthy volunteers have no disease that could affect how the drug is absorbed, metabolized, or cleared. This removes confounding variables and makes it easier to compare the two drug versions directly. If you tested in patients with kidney or liver disease, differences in drug handling could be mistaken for formulation differences. Once bioequivalence is proven in healthy people, the drug is approved for all populations.

Can a generic drug fail bioequivalence even if it’s the same active ingredient?

Yes. Two drugs can have the same active ingredient but different inactive ingredients (fillers, coatings, binders), which affect how quickly or completely the drug is absorbed. A poorly designed tablet might dissolve too slowly or too fast, leading to a lower Cmax or altered AUC. That’s why generics must undergo full bioequivalence testing-even if the active ingredient matches exactly.

Hannah Taylor

December 20, 2025 AT 17:12Cara C

December 22, 2025 AT 14:47Grace Rehman

December 23, 2025 AT 14:41Orlando Marquez Jr

December 23, 2025 AT 18:54Jackie Be

December 25, 2025 AT 13:50John Hay

December 25, 2025 AT 19:26Jon Paramore

December 27, 2025 AT 05:48Swapneel Mehta

December 27, 2025 AT 12:28Cameron Hoover

December 27, 2025 AT 21:30